Diastasis recti symptoms and how to treat it

Abdominal muscles don’t always snap back into place after having a baby, and that belly bulge may be a sign of diastasis. Here's how to knit those abs back together.

Model Photo: Stocksy United, Collage: Roberto Caruso

Your 10th anniversary is a milestone worthy of a night out. Sonia Sakos*, a mom of two kids ages four and seven, was ready to celebrate when she left work and hopped on the subway to meet her husband and the sitter at home.

Her mood changed when a well-meaning commuter eyed her midsection and offered a seat. Sakos declined, embarrassed, and shuffled along to another part of the train. But it happened again—and then once more—before Sakos, now mortified, reached her stop. “I got home, dropped my bag and burst into tears. I felt so awful, we didn’t go out that night after all,” she says.

class="p3">Though it had never happened in such rapid succession, this wasn’t the first time someone assumed Sakos was pregnant long after she’d had her last C-section. Having suffered these misunderstandings for years, she came to resent the gentle slope of her belly and decided she had to do something about it. Through a mothers’ group on Facebook, she found a physiotherapist who specialized in postpartum diastasis recti, a condition she (correctly) suspected she had.

What is diastasis recti?

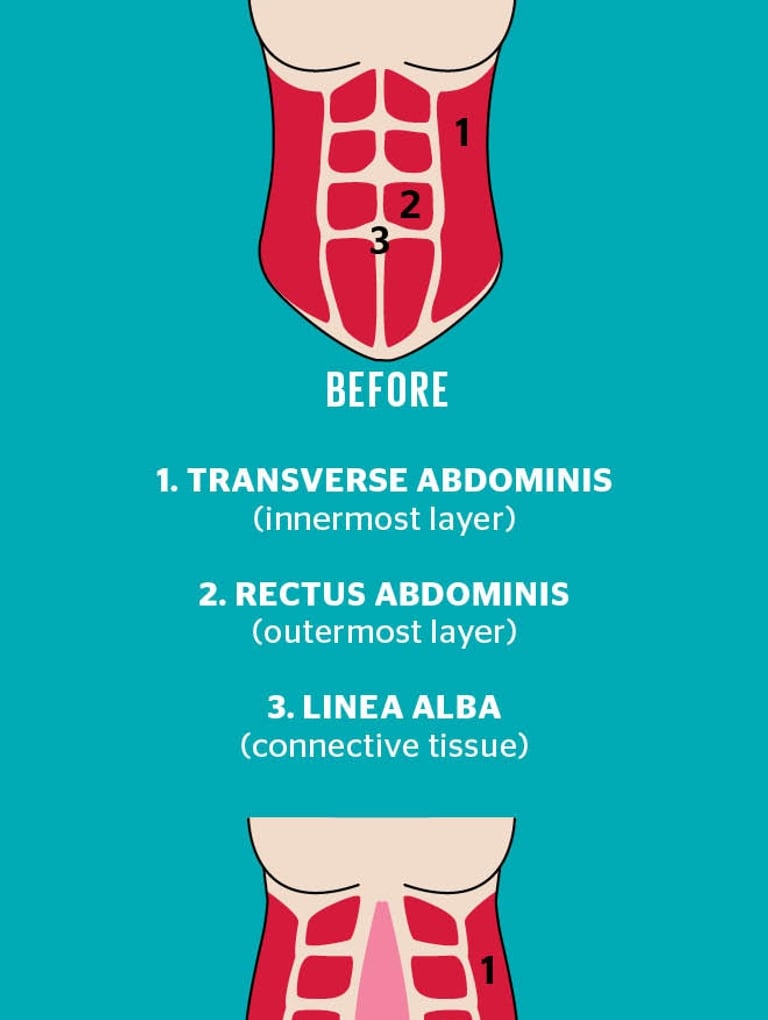

Also known as abdominal separation, diastasis recti occurs when the rectus abdominis—the two large vertical banks of muscles that meet in the centre of your abdomen (known as the “six-pack”)—pull apart from their attachment point, the linea alba that runs down the body’s midline. The largest of the abdominal muscles, the rectus abdominis works together with the pelvis and lower back to help you move and transfer weight through the pelvic area. It also forms part of a wall of muscle that holds the uterus, intestines and other organs in place and lends support to the pelvic floor. Under pressure from a growing baby, these muscles stretch and thin, separating from the connective tissue that binds the abs together.

If you’ve carried a full-term baby in your belly, chances are you’ve experienced some degree of separation. “It’s definitely the norm as the baby is growing and hormonal changes affect the connective tissue, allowing it to relax,” explains Katie Hauck, a Toronto physiotherapist who specializes in pelvic floor rehab and treating patients with diastasis. The likelihood of developing a diastasis, she says, increases for those who are pregnant with multiples, who have had recurrent abdominal surgery (like a C-section) and who have had more than one pregnancy (the theory being that our bodies are quicker to stretch out and to assume the pregnant form in second and subsequent pregnancies). In rare cases, the separation can be so bad it causes a painful hernia, which occurs when organs poke through the separated abs and push against the skin. Thankfully, this isn’t the norm.

Diastasis recti symptoms

So how do you know if your abs have parted ways and are reluctant to meet again? Although diastasis isn’t painful and is not typically obvious until the postpartum period, it can sometimes be detected around the 25-week mark during pregnancy via a physical exam or ultrasound (by late pregnancy, when pressure on the abdomen is at its peak, diastasis is tricky to diagnose). Elisabeth Parsons, a personal trainer who owns Core Expectations, a pre- and postnatal in-home ab rehab service in Toronto, says the telltale (and potentially startling) sign during pregnancy is when the belly takes on a cone- or dome-shaped look when you activate your ab muscles as you’re leaning back on the couch or trying to sit up in bed. (It can appear as a divot or valley when the body is at rest.) This shape often indicates there is too much strain on the abdominal wall, says Sarah Zahab, an Ottawa-based kinesiologist and exercise physiologist.

“The fact that you get a diastasis is not in itself so awful—it’s what your body is supposed to do to accommodate the growth of your baby,” Parsons says. “It’s bringing it all back together and restoring function in those muscles [postpartum] that’s important.” While Hauck recommends women see a physiotherapist to have their core strength assessed during pregnancy (physios will send you home with some belly-friendly exercises to lessen back pain), the reality is diagnosing separated abs during pregnancy isn’t often done. Most women call on experts like Parsons in the weeks and months after delivering, when they notice the protruding belly and a general feeling of weakness in their core. “A lot of moms come to me and say it feels weak when they go to pick up something like a laundry basket—it feels like there’s nothing there,” Parsons says. Other signs of diastasis include incontinence that continues more than eight weeks postpartum (separated abs can often cause pelvic floor dysfunction, which can lead to urine leakage, constipation and pain during intercourse), lower back pain and a four-months-pregnant look (for several months or years after giving birth) or that same dome-like bulge in the centre of the abdomen when you cough or sit up from lying down.

“Feelings of weakness and back pain after pregnancy are common, so diastasis is something that often gets missed,” says Hauck. While postpartum women in France receive a doctors’ exam to check for diastasis before they leave the hospital—as well as state-sponsored physical therapy sessions to rebuild their cores—doctors in Canada don’t routinely examine for the condition (or for overall pelvic floor health, for that matter). Fortunately, it’s easy to check yourself—a good first step if you’re trying to decide whether to invest in a physiotherapy assessment.

First, Hauck says, lie on your back with knees bent, feet flat on the floor. Starting at your belly button, poke a few fingers straight down into your abdomen. Slowly lift your head off the floor, as if you’re about to do a crunch. “What you want to feel is the edge of your abdominal muscles hugging or squeezing your fingers,” she says. “If you don’t feel it with two or three fingers there, add more fingers until you feel a hug.” A gap of one or two fingers is normal and doesn’t require treatment; the gap may or may not close, but it’s unlikely to inhibit healthy function, Hauck says, unless it’s accompanied by other issues, like incontinence or low-back pain. In that case, or if the gap is larger than two fingers, it’s time to see a physiotherapist who specializes in pelvic floor treatment—especially if you plan to have more children. A stronger core will make subsequent pregnancies and postpartum recovery easier.

How to treat diastasis recti

Not everyone needs special care. Don’t freak out if you’re less than eight weeks postpartum—healing takes time. During this period, many women are lucky enough to have what she calls “spontaneous recovery,” meaning the connective tissue linking the large ab muscles knits back together or comes close enough to restore normal core function. Postpartum wraps or corset binders, meant to support stretched ab muscles, may help in those first eight weeks, but Hauck cautions they’re not a miracle cure. “It would be very similar to wrapping your ankle if you rolled it,” she explains. “It’s a way to give temporary support while those muscles aren’t working as well as they should be.” But be careful, Hauck adds. When bound too tightly, postpartum wraps can actually worsen your core by putting more pressure on the pelvic floor, which already struggles to function well when abs are weak.

Those who aren’t fortunate enough to recover spontaneously typically won’t know they have a problem until symptoms arise in the weeks, months and sometimes years after giving birth. In Sakos’s case, it was the lingering belly that no amount of conventional exercise or virtuous eating could shift. “Women will say, ‘I look like I’m still five months pregnant. I’ve lost my weight, and I’m back in my normal jeans, except for my tummy,’” Parsons says. “Usually it’s not baby weight. It’s diastasis.”

Before you get down on the floor to exercise your belly away, you should know that most common core exercises—crunches, abdominal twists and, when done incorrectly, planks—can all worsen the condition. “The best ab exercises [for] are the ones that target the deep core stabilizers,” says Zahab.

She’s referring to the transverse abdominis, the deep abdominal muscles that form the foundation of a strong and healthy core. Many of the exercises used to target them—diaphragmatic breathing, lying on your back with your knees up and core engaged or marching in place with your core braced, for example—won’t even make you sweat. “The exercises feel kind of mundane. It’s not the meat and potatoes of the workout,” says Bonnie Burlton, a 34-year-old former Canadian national pentathlete who lives in Gatineau, Que. She began seeing Zahab for help with correcting her diastasis during and after her first baby and ultimately left stronger than she was before her pregnancy.

As you deep-breathe your abs back together, remember: Regardless of how long you’ve had a diastasis, it can be corrected. Zahab has helped clients regain their full core function and lose their persistent belly up to 10 years after their last baby. Only in rare cases, when physiotherapy doesn’t result in recovery, is surgery necessary. (Family doctors won’t recommend going under the knife unless there’s a hernia to repair.) In what’s called abdominoplasty or, more specifically, a muscle plication (a.k.a. a tummy tuck), the muscles are surgically stitched back together. If that seems like an easy way out, though, consider the price tag: Most surgeries start at $8,500 and are only covered by provincial health insurance if they’re medically necessary. Hernia repair makes the grade, but poor abdominal muscle function does not. Recovery from abdominoplasty can take a couple of months; for the first two weeks, doctors discourage patients from lifting anything, including their babies. After six weeks you can resume most normal function, but not your ab workout.

The option that’s easiest to stomach? Find a good specialist. Look for a physiotherapist trained in pelvic floor therapy, or a personal trainer with a background in kinesiology, exercise physiology or who has taken an accredited course on treating abdominal diastasis. “It’s never too late to get it looked at,” Hauck says. “There’s always something you can do.”

* Name has been changed

Weekly Newsletter

Keep up with your baby's development, get the latest parenting content and receive special offers from our partners